Misteri d'Elx

Music

The most outstanding artistic aspect of the Mystery of Elche is the musical one. Elche’s drama is all sung and it contains melodies that, according to the experts, come from different times: there are chants in it with a clear medieval background, a very interesting renaissance influence, and even adornments and insertions from the baroque, and even latter times, can be found in it. However, its musical unity is extraordinary, as different studies and research on this matter have pointed out. Research that has been carried out from the early years of the 20th century by musicologists and scholars such as Felipe Pedrell, Óscar Esplá, Samuel Rubio, Ismael Fernández de la Cuesta, José M. Vives or M. Carmen Gómez Muntané.

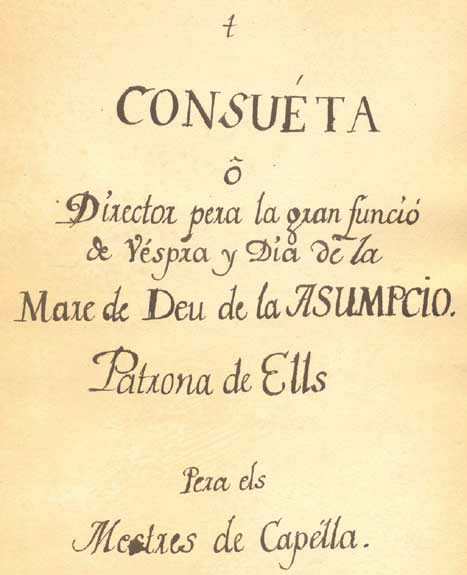

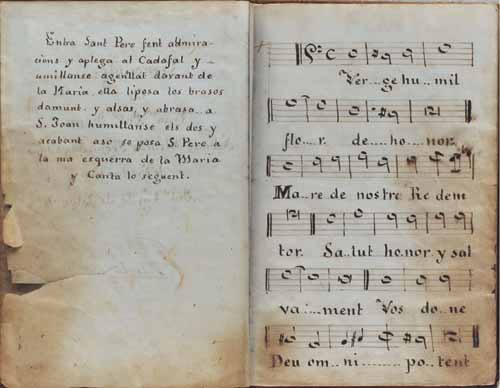

The chants of the Mystery can be roughly classified in monodic and polyphonic. Really, from the twenty-six musical pieces we find in the historical consuetas of 1709 and 1722 –with the exception of the psalm In exitu Israel d’Egipto, which is repeated three times in the second act-, ten are monodic and sixteen polyphonic, although in both cases some of the melodies are repeated with different literary texts.

Some of the monodic chants- more abundant in the first act of the play- show a clear influence from medieval Gregorian. In fact, the consueta itself remarks that one of the chants of the Virgin Mary must be sung in the tone of the Vexilla Regis, hymn compsed in the 6th century in honour of a fragment of the Cross of Jesus Christ. In the same way, there have been detected certain points of contact between some of the chats of Saint John and Saint Peter and the Gregorian hymn Victimae paschali laudes. This technique consisting in adapting new literary texts to existing scores, religious and popular –known as contrafactum- was very common in old theatre representations, because, in this way spectators, which were familiar with the original melodies, were soon identified with the staging. In other cases, the abundant melismatic ornamentation of the songs, accumulated through centuries, hinders a clear identification of the original version. The clearest example can be found in the melody of the angel in the cloud or “pomegranate”.

There has also been found certain concordance between the polyphonic chants of the Mystery and carols and other songs compiled in the Musical Songbook of Palace. This shows that during the renaissance musical reform the drama underwent in the 16th century, not only original pieces specifically composed for it were added, but also a contrafactum of already known melodies was also added.

Thanks to some notes found in the consueta of 1639, we know the name of three of the composers who took an active role in the above mentioned polyphonic reform. They were a certain Ribera, who, with certain precautions, has been identified as Antonio de Ribera, singer of the Pontifical Chapel in Rome between 1513 and 1523. Other scholars, however, think this Ribera was a tenor in the Imperial Chapel of Maximilian II of Austria between 1566 and 1567.

Another of the authors we know of the polyphony of the Festa is the canon Pérez, identified by the experts as Ginés Pérez (1548-1600), chapel maestro of the cathedral of Valencia and canon in the cathedral of Orihuela.

Finally, Lluís Vich is mentioned, organist of the Elche church of Saint Mary and its first known musical chapel maestro (between 1562 and 1594).

The chapel maestro of the royal chapel of Madrid, Juan Bautista Comes (1582?-1643) was also linked to the music of the festa. According to the consueta of 1625, he composed a piece to replace the one the Holy Trinity sang. This piece was finally not included in the play and, although the above mentioned libretto contains the verses of the chant, the score has been lost.

Nowadays, the chants in the Mystery - with the exception of the Araceli, which is accompanied with guitar and harp - are interpreted a cappella. We also know that a wind instrument – mostly a fagot- used to accompany some of the motets in the play, replacing the bass voice, as late as the first third of the 20th century. Besides, there are documents that prove the existence of an important chapel of players and singers in the church of Saint Mary of Elche, chapel that had its most outstanding epoch in the 18th century. Amongst those musicians, who were called in the consuetas “ministriles”, as they appeared in the Misteri, we could find players of different instruments, such as xeremia (like a flageolet), cornet, flute, oboe, sackbut, horn, violin, harp, etc., as well as professional singers who were sometimes hired in other cities. This professional musical chapel disappeared in 1835 and, in order to ensure the continuity of the representations of the Mystery, local amateur singers, following the great choral tradition of the village, took charge of its representation.

In the present time, the assumptionist drama is represented by the members of the Chapel of the Mystery of Elche –formed by about sixty adults and thirty children. And, although none of them, except in some very occasional circumstances, is a professional singer, the quality of their voices and the magnificent blend they achieve can be enjoyed in the yearly representations of the drama and in the extraordinary concerts they offer.